Words That Used to Mean Other Things

March 2023: A letter for people who want to communicate and to understand.

Dear family, friends, and Internet strangers,

This month, I’m writing to you about something that’s interesting to me for its own sake, and about some life applications I’ve run into as I’ve ruminated on the topic: words, and how context changes them.

If language for its own sake doesn’t grab you, you still can’t escape the need for clear communication. I’ve been thinking about all the things that get lost as we try to speak to one another. You think you’re speaking the same language as someone else, but maybe you aren’t. You read something from only a few decades ago, and think words mean the same things they once did, but they don’t. You think the same word in academic circles means what it does colloquially; you think you can use the same word for fizzy drinks in the Midwest as you did in New England; you think you have any idea what teenagers mean when they write on Tumblr.

There is a danger in getting too hung up on individual words, but there is also a danger in making ignorant assumptions about them. If language isn’t interesting to you, yet, I hope you can see it through my eyes as you read this letter. There are hidden treasures in every word, and what we call English, whether in its American form or otherwise, carries secrets from many nations, many centuries, often hidden in plain sight.

When I turned 15, my grandma bought me The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology.

She didn’t write a message in the front, because she wanted me to be sure I really wanted it before she marked it at all, and she died with little warning just a few months later. She wanted to be wise in gifting something like that to a teenager. I get it; who wants a giant, expensive etymology dictionary at 15 years old? I’d asked for it, but even I couldn’t be sure it wasn’t just one more hobby I’d forget about shortly thereafter. So I appreciated her wisdom, and we waited, and then she was gone.

I wish I’d insisted she write in it, knowing what I know now. I also wish I could tell her that I use it all the time.

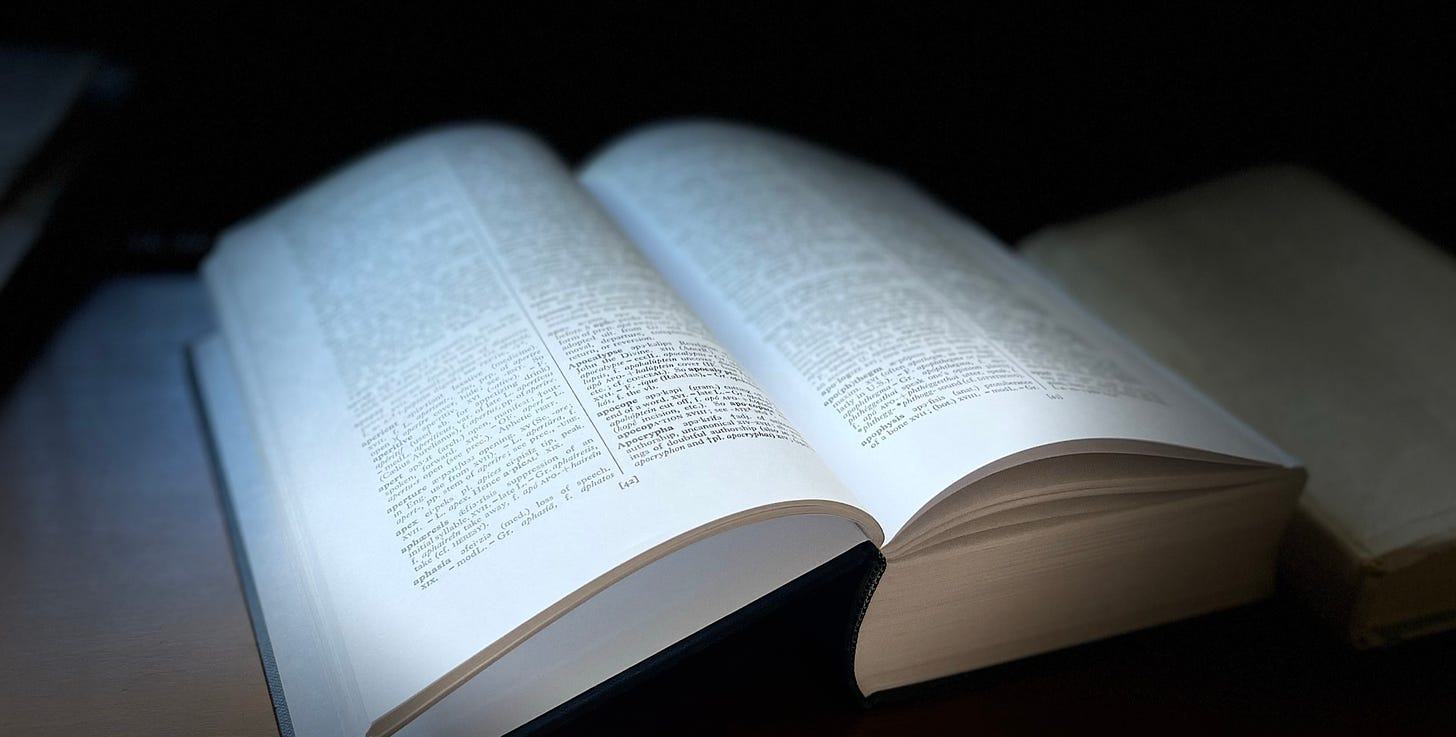

I do look up etymology online when I want a quick answer, but it can’t compare to the adventure of picking up my gorgeous brick of titanium-white pages, looking up one word, and meeting a dozen others on the way.

That’s how I found out “apocalypse” hasn’t always referred to the end of the world.

I ran into the word in the big etymology dictionary while seeking something else, probably in the last year or so, and found it unexpectedly capitalized, its definition given only as, “Revelation of St. John the Divine.” That is, the last book of the Bible, the Book of Revelation.

This dictionary is still less than 20 years old, but the copyright date for its content is 1966; the definitions aren’t necessarily current, adding another dimension to the history within.

The Greek words on which “apocalypse” is ultimately formed literally mean, in essence, “to uncover” or “to disclose”—to reveal—thus, as a noun, “revelation”. “The Apocalypse of John” is, or was, synonymous with “The Revelation of John”.

We think of the Book of Revelation as pertaining to the end of the world as we know it, so we English-speaking humans came to think of “apocalypse” as referring to the same. I don’t know why the meaning of “revelation” was essentially retained (e.g., “I had a revelation”) while the meaning of “apocalypse” wasn’t. Maybe because we use “reveal” as a verb?

I was very excited about this little discovery.

Another word-history lesson that I found exciting in the last couple of years began when I saw a particular Instagram post by artist Makoto Fujimura. He’s a Christian whose abstract art redefined my view of the concept and value of non-figurative painting. He posted about a piece from his series on the four gospels, the painting he named “Luke - Prodigal God”, referencing a book by Pastor Timothy Keller.

“Prodigal God?” I thought. “God doesn’t leave, and Mako isn’t a bitter ex-Christian. Do I not know what ‘prodigal’ means?”

Sure enough, it refers to wasteful, reckless spending, not to running away from one’s family to gallivant in sin, nor to returning after such an act. The phrase “prodigal God” refers to the ways God gives lavishly—even giving His own Son (see Romans 8:32 in Paul’s letter to the Romans).

Since Jesus’s parable of the prodigal son seems to emphasize the son’s running away and sinning, where the reckless spending of his inheritance is just one piece of that, and since we rarely have cause to use the word in unrelated situations, we associate the word “prodigal” with running away as well. Or, with the return from such. Note that the word “prodigal” is in the section heading added by translators, not the parable itself.

And while we’re speaking of change, “catastrophe” entered my radar this year, and I sought answers in etymology dictionaries online; the word came up and I seemed to remember it once had a somewhat different meaning.

The dénoument of a drama, evidently, was an earlier meaning, and the word literally refers to a sudden turning. Etymonline.com uses the phrase, “reversal of what is expected.” But after a couple centuries, it began to mean “sudden disaster”, how we use it now.

(Bonus: You can see the “apo-” from “apocalypse”, whichs means “off, away from”, combine with the “strophe”, for turning, in “apostrophe”. If you’re curious about that, investigate further: etymonline.com/word/apostrophe)

What stands out to me is that these words became associated with something in their context. Rather than the words commanding or deciding how things are understood, the context decided, over time, how the words are understood.

This is true for so much more than words.

“This reminds me of something that hurt me before; I’m now feeling defensive and cannot hear what you’re saying.”

“You sound, look, or dress like someone I know, and I will make assumptions about you based on such things.”

“I reject this reality because it doesn’t fit the context of my worldview.”

“That person has this job, that education, this apartment, that number of kids. I assume many things based on other people I know, or what I see on TV about those characteristics.”

“I see the context, so I think I see the thing clearly.”

Context clues are great, and truly helpful. But they aren’t always enough information. As a writer, I want—I need—to communicate. As a person, I make assumptions constantly, without realizing.

Assumptions can destroy communication like termites destroy homes: insidiously.

I ran into a quote a few weeks ago by author and comedian Jacqueline Novak, from her memoir How to Weep in Public, in which she describes the mismatch between our words and what people understand:

“No matter how good you are with words, it’s inevitable that meaning is lost between your mind and someone else’s. Trying to communicate is like throwing a cup of water at a thirsty person’s face. It’s better than nothing, sure, and a teaspoon of water might hit their lips, but oh, God, there’s just so much water in the grass.”

I admit, I haven’t read the book and don’t have the context for that quote.

Yet it illustrates in brief what I’m trying to communicate at length.

I thought I was good at communicating ideas, and I’m finding it’s harder than I thought. I have to imagine what the receiver of my words already knows, believes, and understands, in order to get a blurry picture of how my words will be understood, how to change my words to align to their soul.

Let me clarify something. Language is used for communication, and if the meaning of a word changes over time, it’s absurd to insist on using an obsolete meaning of it without clarifying that use every time. With the clarification, it is possible to communicate more than we can with only this year’s use of certain vocabulary. Without such clarification, it is not communication, just pedantry.

I solve nothing by insisting on returning to the old use of “apocalypse”. “Prodigal”, maybe, since we don’t use it with clear meaning in any context; in my experience people say it to mean, “in some quality like that one son in the parable.” But it serves no one for me to begin a conversation with, “This morning, while reading, I had an apocalypse!”

It is possible to speak without considering the audience. If you want to vent, or to rant, or to express your feelings for their own sake, maybe that’s what you do. But if you want to be understood, the audience matters. We all know it’s necessary to speak a person’s language to be understood. What gets lost is how much that language depends on its context.

People like to point out that learning a second language requires learning its cultural context. You know what? It’s true. They’re totally intertwined. It does frustrate me, as I want words to simply mean things I understand from my own culture and existence. Yet the meaning of a word is drawn at least in part from its context, and its context can change it permanently.

And our context can change us.

Consider your context. Is it changing you? Are you changing for the better? Why?

Where do you assume meaning or intent based on the context, rather than on the person or what that person actually said?

As you read, write, speak, and listen, how aware are you of the potential gap between what is said and what is heard? Are you speaking to speak, or to be understood? Are you listening to what is being said, or to what you expect to hear?

Writing Updates

It’s been another slow month as far as my own writing goes. I’ve been doing pretty well health-wise for weeks now, and am catching up on various stuff where I can.

Things I Found Useful This Month

This month’s Chicago Manual of Style Q&A answers two questions on a timely topic: how do you properly cite AI-generated works? Because the answers have broader implications, I thought someone out there might appreciate them. You may at least find them interesting if recent AI developments have caught your attention.

I learned that JSTOR lets anyone who registers read a certain number of academic articles for free each month—and that number right now is 100. I don’t know about you, but I often click links for helpful-looking journal articles in search engines only to get an abstract and a paywall rather than the article itself. If you’re not a student, can’t get access through your library, and don’t otherwise have broad access to journal articles, enjoy this benefit of free registration at JSTOR.

I found out it’s possible to get a discounted Spotify Premium annual subscription (works for Single only, not Duo, Family, or Student). They don’t make it simple like most subscription services, where you can just choose the annual option at checkout. You have to purchase a gift card from a place like Amazon (physical or digital), GameStop, or Best Buy and go to spotify.com/redeem to use it. The discount was significant enough for me to stop using Spotify’s annoying ad-supported version and actually pay something, so maybe one of you would also appreciate this. (None of these are affiliate links, so do whatever you want as far as clicking, going to a store, listening to a thousand ads on free Spotify this year, idc.)

That’s it for now! I hope you found something in this letter useful, interesting, or beautiful.

Until April,

Rae

p.s. If you enjoyed this month’s dive into English etymology, you may also enjoy knowing that there exist something called cranberry morphemes.